|

C. B. Nieuwenhuis

People gathered at pasar (market) at Bukittinggi (Fort de Kock). Sumatra. 1907 |

C. B. Nieuwenhuis was a Dutch photographer active in Sumatra from about 1890 until his death on april 20, 19221. Once established there, he quickly came to be considered one of the island's best photographers. His fame depended largely upon his outstanding views of the Sumatran landscape, but landscape photography is only one theme in his varied body of work. A man of great talent, Nieuwenhuis kept up with technical developments of the medium and adapted his business to changes in the consumer market for photographs.

Christiaan Benjamin Nieuwenhuis was born in Amsterdam on July 4,1863. He spent his youth in Amsterdam, and in1883 he moved to Hardervijk. His early training in music enabled him to travel to Jakarta, following a young woman, Frederika J. S. van Ginkel, whom he had met during her leave in the Netherlands. He is reported to have left for Jakarta in 1884 as a member of the Royal Military Band. It was there, a few years later, that he learned photography at the studio of Koene & Co., which had been opened in mid-1887. It is not known how long Nieuwenhuis stayed in Jakarta, but it may have been until at least 1888.

By 1892, he had moved to Padang, Sumatra, where he set up his own studio in the side room of the house he designed and built at the Bentegweg. He married Frederika the following year. He placed a sign advertising his studio on the front of the house, exhibited his pictures on the outer veranda and ran advertisements in local newspapers. He made studio portraits in the carte-de-visite, cabinet and boudoir formats, using the more sensitive gelatin dry plates and faster lenses to shorten the posing time for his subjects. His customers were both Europeans and well-to-do native residents; he also received commissions to make official group portraits of Dutch colonial authorities.

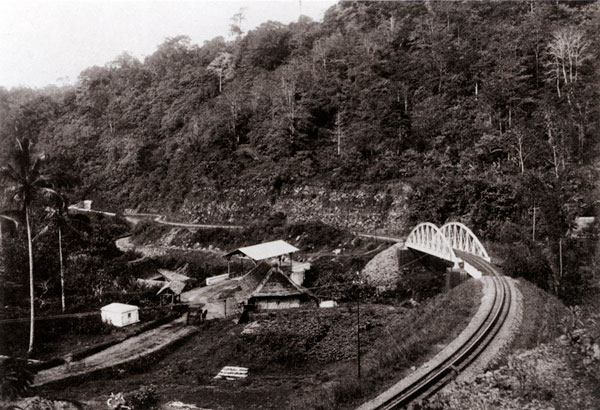

In addition to making these portraits, Nieuwenhuis also sold views of Sumatran landscapes and towns that he made during photographic excursions into the countryside. He traveled extensively throughout Sumatra, from Sabang in the upper north to Palembang in the south. He consistently took his pictures from elevated and distant points in order to get overall views; street scenes of towns are rarely found. Nieuwenhuis' views show the contrasts of colonial influence and traditional life on the island. Some images that were especially popular among tourists depict only the forms and beauty of the landscape, but many illustrate his interest in showing the technical achievements of the modern time. He often photographed iron bridges and harbor yards, as well as the West Sumatran railway line and its stations.

The photographer also had an interest in ethnographic subjects he came across on his travels, and he made architectural views in Batak and Minangkabau villages. Locals posed for him with their tools and utensils, in their traditional dress, and Nieuwenhuis made some excellent anthropological group portraits. At one point prior to 1897, he received an assignment from the Dutch colonial government to photograph on the Mentawai Islands, on the west coast of Sumatra.

On occasions such as this he took anthropological pictures for his own use. In an account of his trip, Nieuwenhuis says that he found it difficult to photograph there since the people had not yet had contact with photography and were distrustful of the camera. Nieuwenhuis distracted them with small gifts and had to work patiently, since they would not remain still for long. In one instance, he gave a Radja an old military uniform to convince the man to pose for him. Nieuwenhuis later traveled to Nias, where he portrayed nobles and warriors posing in their most precious attire and full fighting kit. Despite their general interest, the real ethnographic value of these pictures is clearly doubtful.

Nieuwenhuis also made individual anthropological portraits in his studio. These images show isolated native "types" of Sumatra and Nias in a European setting. He sold prints of these ethnographic and anthropological pictures, along with his topographical views, to Europeans as souvenirs of Indonesia. The sales extended his income from his commissioned work, and his photographs were soon published in popular travel articles and scientific essays.

Always looking for enterprising ways to extend his photographic business, Nieuwenhuis asked the military governor, Van Heutsz, for permission to join a military campaign in Aceh, where war had broken out between natives and the colonial army. During January 1901, he spent nearly two weeks with the Royal East Indies Army on an expedition to Samalanga.

Nieuwenhuis and others had already taken pictures showing the military presence in Aceh, but they were static pictures of military settlements and portraits of soldiers that did not show the actual fighting. His Samalanga pictures are unusual because they were made while the conflict was going on. If his porters had not fled with his camera as soon as the actual man-to-man combat began, he would likely have taken pictures of the fighting itself, but he still can be considered the first actual war reporter in Aceh. Nieuwenhuis soon published an account of his experiences that included twenty-two pictures.2

The images served then as propaganda for the Dutch Army, and today they are symbols of Dutch military superiority in Indonesia. In a 1902 review of the book, the images were praised for their informative value. Although the reviewer did not regard them as beautiful, he considered them an interesting alternative to the written reports of the war that enabled readers to get a real view of how things looked.3 Later in 1902, Nieuwenhuis toured through Java with the amateur archaeologist Isaac Groneman to take archaeological pictures. Unlike earlier photographers, he depicted Borobudur and other temples in an artistic way, rather than presenting details for archaeological study.

By 1905, Nieuwenhuis had moved from Padang to Banda Aceh, and at the same time he advertised himself as a photographer in Medan. Medan was an important economic center where some of the best studios were established, including the Sumatran branch of Singapore's G.R. Lambert & Co. and the studio of Lambert's former employees, Kleingrothe & Stafhell. Nieuwenhuis did not want to miss economic opportunities in this center, and he traveled between the two towns. His studio was at the house of friends, the Reep family, and he stayed there several times a year. Nieuwenhuis' wife had died in 1898, and by this time he was taking care of his three children as well as his mother-in-law. He often took his children along to Medan to enjoy a holiday there and play with the Reep children.

In Banda Aceh, his firm issued picture postcards with views and portraits of Sumatrans. After 1910, Nieuwenhuis moved back to Padang, where he issued a series of postcards called Sumatra's Westkust (Sumatra's West Coast) as both photogravures and bromide prints. He also started reprinting and making enlargements of older views. This change in focus for his business was due to the growth of amateur photography, which lessened the interest in commissioned portraits, but the demand for quality views by professional photographers remained strong. In 1916, Nieuwenhuis photographed ethnographic artifacts from Aceh before they were sent to a museum in the Netherlands, and in 1918 he issued a portfolio, also called Sumatra's Westkust, that contained twenty-four photogravures of his most successful views.

In his later years in Padang, Nieuwenhuis made some excellent ethnographic and anthropological pictures of the Batak people. These differ from his earlier images in that they are more lively, showing people in action, at the market or dancing; they also show a more realistic vision of how life had changed within a decade. These images, in various sizes, were sold to tourists and were compiled into albums. Nieuwenhuis' daughters, Christine and Hermine, assisted in producing the albums. His elder daughter, Christine, continued to operate both the studio in Padang and the branch in Medan after Nieuwenhuis' death.

NOTES

1. Biographical information included in this essay has been taken from internal evidence in C. B. Nieuwenhuis' photographs, conversations by

the author with Mr. and Mrs. Cornelis-Niewenhuis and with Steven Wachlin, and from the following sources:

Maurik, J. van, Herinneringen van een totok, Indische typen en schetsen, Amsterdam 1897, 27-33.

Anneke Groeneveld, Toekang Potret: 100 Years of Photography in the Dutch Indies, 1830-1930, Museum of Ethnology, Amsterdam/Rotterdam, 1989. Wachlin, Steven, Commercial Photographers and Photographic Studios in the Netherlands East Indies 1830-1940: a survey, Amsterdam, 1989. Zweers, Louis, Sumatra, Kolonialen, koelies en krijgers, Houten, 1988, 12,105,127,160.

2. Nieuwenhuis, C De Expeditie naar Samalanga (Januari 1901), dagverhaal van een fotograaf te velde, Amsterdam, 1901.

3. Review in Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk, Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2nd S-, XIX (1902), 436-437.

|

C. B. Nieuwenhuis

People gathered at pasar (market) at BukGroup of villagers from the island of Siberut,

of the Menawai island group, off the south coast of Central Sumatra, c. 1910 |

|

C. B. Nieuwenhuis

Nias warriors in festive dress in front of their adat houses, c.1900. |

|

C. B. Nieuwenhuis

Bridge at Anai Kloof, Sumatra, c. 1900 |

|

C. B. Nieuwenhuis

Distant view of river in Pedang, Sumatra, c. 1900 |

| next paper | about Anneke Groeneveld

| contents page | asia-pacific photography | photo-web | contacts

|